What motivates my research?

I conduct research with the intention of (1) helping to develop solutions to important applied conservation challenges, while (2) furthering basic understanding of eco-evolutionary theory. As a result, I have dedicated much of my career to studying plant invasions. Invasions are one of our top ecological and economic challenges, which makes understanding what drives their spread and their impacts critical to informing effective management. Additionally, invasions represent fascinating evolutionary experiments conducted on an unprecedented global scale. For example, I use invasions to investigate how different selective pressures can drive different evolutionary trajectories, as plants often experience consistent environmental differences between their native and introduced ranges. Invasions therefore present unique, replicated opportunities to increase our understanding of eco-evolutionary theory, which can have strong implications for introduced and native plants alike.

Under this umbrella, I am largely motivated in my research by the following, overlapping interests:

I conduct research with the intention of (1) helping to develop solutions to important applied conservation challenges, while (2) furthering basic understanding of eco-evolutionary theory. As a result, I have dedicated much of my career to studying plant invasions. Invasions are one of our top ecological and economic challenges, which makes understanding what drives their spread and their impacts critical to informing effective management. Additionally, invasions represent fascinating evolutionary experiments conducted on an unprecedented global scale. For example, I use invasions to investigate how different selective pressures can drive different evolutionary trajectories, as plants often experience consistent environmental differences between their native and introduced ranges. Invasions therefore present unique, replicated opportunities to increase our understanding of eco-evolutionary theory, which can have strong implications for introduced and native plants alike.

Under this umbrella, I am largely motivated in my research by the following, overlapping interests:

Accountability in invasive species management

Invasions should only be suppressed if they have negative ecological or economic impacts and if suppression is expected to mitigate those impacts. Understanding the impacts of both invasions and our efforts to control them is therefore critical for informing effective management. However, despite important progress towards understanding these impacts, we still often lack the site-specific understanding (i.e. quantitative evidence on the relative cost vs. benefit of different management actions) needed to inform local management decisions. To this end, I am developing a conceptual framework that outlines the responsibilities that scientists, managers, and funders can adopt to overcome traditional challenges and hold each other accountable to an evidence-based framework on invasive species management. I designed this framework to recognize that, moving forward, we need to better support managers—who have limited time and resources—to collect evidence of the impacts of invasions and their management.

In addition to a conceptual framework, I am also passionate about developing more accurate, efficient, and cost-effective tools to assess these impacts. For example, I am collaborating with Holger Klinck and his team at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology to use stationary recorders to monitor how bird, frog, and toad calls change in response to invasions. As part of this project, we are working with the Chemnitz University of Technology to adapt BirdNET (a machine learning algorithm) to efficiently and effectively automate wetland bird, frog, and toad species identification. We are also experimenting with using microphones tethered to drones to be able fly over wetlands, and spatially pinpoint exactly where individuals are calling. Moving forward, we hope to overlay the spatial map of calls with aerial photography, which will allow us to disentangle exactly which species use which types of vegetation within these wetland habitats.

|

|

Rapid evolution of plant populations

|

In today's world of increasingly rapid global change, understanding how (or even whether) plants adapt and evolve to novel environmental conditions is critical for both managing problematic invasions as well as conserving the native species we want to protect. Consequently, I am fascinated by how local adaptation (especially to climate and insect herbivory) can drive different evolutionary trajectories in a plant's native vs. introduced ranges. I have explored this in three systems so far:

For my PhD, I investigated whether between-range differences in performance of common mullein were driven by adaptation to herbivory or climate. My collaborators and I found that a genetically based cline in performance in common mullein's native range (seeds produce smaller rosettes the cooler and drier their climate of origin) but not in the plant's introduced range (seeds produce large rosette regardless of their climate of origin) drives plants, on average, to be larger in their introduced rather than native range (read our Journal of Ecology article here to learn more). |

As a postdoc and then research associate, I explored whether local adaptation to climate helps explain genetic variation among populations of Japanese knotweeds (Reynoutria japonica, R. sachalinensis, and their hybrid R. x bohemica) as well as the invasive and native subspecies of Phragmites australis. As an associate professor at UNCW, me and my team continue to expand upon this research.

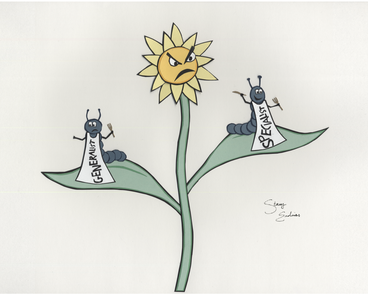

Plant-insect interactions

Plants form the basis of all terrestrial ecosystems, and insects consume more plant tissue than all vertebrates combined. Insects are therefore critical to understanding the abundance and distribution of both plants and the animals that depend on them. As a result, I am fascinated by what drives differences in resistance and tolerance to insect herbivory at the within-plant, between-plant, and among-population level across plants' native and invasive ranges. I am particularly interested in whether both a shift in the degree and type of insect herbivory drives selection after plants are introduced to a new range (check out the video and its associated graphic below for my 2016 3-minute thesis on this topic). During my PhD, I found that for common mullein, young leaves are better defended than old leaves, but that between-range differences in just how much better defended young leaves are than old leaves are likely driven by factors other than adaptation to between-range differences in herbivory.

As a postdoc and then research associate, I investigated variation in resistance and tolerance to insect herbivory to help inform invasive species management, especially in terms of biological control of invasive Phragmites australis and invasive Japanese knotweeds (Reynoutria japonica, R. sachalinensis, and their hybrid R. x bohemica). My collaborators and I, for example, published an article in Biological Invasions explaining 20 years of research supporting the release of Archanara geminipuncta and A. neurica—two highly-specific, stem-boring moths—for control of invasive Phragmites australis in North America. Additionally, I have assessed the impact of insects released to control purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), a common wetland plant invader, now that we are 25 years post-insect-release. I have demonstrated that these insects have not only driven declines in purple loosestrife, but have also resulted in recovery of native plant communities, which is often the ultimate goal of management.

Dispersal ecology

Understanding how organisms spread and disperse has strong implications for managing invasions, disease, and rare populations alike. For my PhD, I used the model system Tribolium castaneum (red flour beetle) to provide insight into a long-standing question in ecology: what influences how far an individual decides to disperse from its current habitat? I found that an individual's phenotype, as induced by juvenile environment, mediates how both individuals and their neighbors respond to their external conditions: the juvenile history of just one-third of the population can drive the dispersal of the entire group (read more in our article in Ecology Letters). I now apply my interest in dispersal ecology in a more applied context. For example, I found that the four insect species released to control purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) were limited by topography (i.e., following prevailing wind directions) ten years after their release, but that thirty years after their release all four species are now widespread throughout central New York.